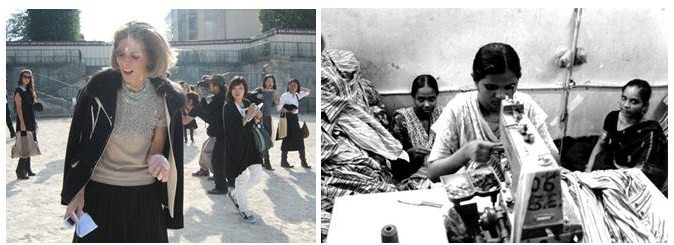

As we mark the 106th anniversary of Triangle (25 March 1911), I wanted to share the work of Canadian artist and activist Robin Pacific. Since 2013 she has been working on a community project to raise awareness on the realities of work and life for garment workers in Bangladesh. In May she is launching TakeActionFAST, a labour rights campaign she has organised with partners in Bangladesh and in Canada (details below).

I first heard of Robin’s work when I was in Dhaka conducting part of my fieldwork in 2015. Recently I was lucky to connect with her and learn a bit more about her work.

Mary Hanlon: To get started, could you tell us a bit about the F.A.S.T. campaign and how it came about?

Robin Pacific: We are now calling it TakeActionFAST (because the Heart and Stroke Foundation launched their own FAST campaign – cheeky!). In 2013 I received some funds from the Ontario Arts Council to do research on possible art projects about who makes our clothes. I turned the research into a collaborative community project and invited 30 women in groups of three to my house. I cooked for them, and gave a 10 minute talk about art, fashion, globalization, free trade and workers’ rights. Then the conversation just flowed. It was at one of these gatherings that someone came up with the idea for a logo called FAST – FAIR living wage, ADULT labour only, SAFE working conditions and No unpaid overTIME.

The idea for a campaign to tell retailers we will pay 5% more for our clothes if those conditions are met evolved over time and went through many variations. The necessity that I must go to Bangladesh if I wanted to speak on behalf of garment workers there also came about during those dinners.

MH: You’ve partnered with various sponsors and supporters. How did these partnerships come about, and how important was it for you to connect with groups in Bangladesh?

RP: This whole project has been about never giving up, and just relentlessly continuing even when it seemed there was no support. So I just kept e mailing people I heard about in Bangladesh, and at UniGlobal, and various Canadian trade unions. When they didn’t answer I emailed them again. When they still didn’t answer, I phoned them! Eventually the first trip came together. We made art with 100 garment workers represented by The Solidarity Centre/Bangladesh led by Alonzo Suson and Bangladesh Workers Solidarity Centre led by Kalpona Akter. We were very, very lucky to work with these outstanding trade unions. It was inspiring and transformative to meet young women who were risking their jobs—and sometimes their lives—to form a union.

If we hadn’t had the support of these two groups I think our visit to Dhaka would have been more or less futile.

We also were very graciously hosted at a luncheon by then Canadian High Commissioner Heather Cruden, and one of her staff suggested we connect with some survivors of Rana Plaza. This too was a profound experience, and humbling – meeting these people whose bodies and psyches were so shattered.

While in Bangladesh and after, I kept meeting artists, individuals, trade union members, members of NGOs, and I also go a little connected to the Bangladeshi community here in Toronto. All of these connections have immeasurably enriched the work I’ve done.

MH: What has been the biggest challenge you have faced so far?

RP: The biggest challenge I’ve faced, in a way, has been my own despair at all those points when things weren’t working out, when it seemed things would never come together. My challenge is not to take it personally and get discouraged when people aren’t interested, or reject various proposals for exhibitions, etc.

MH: As you move forward, what keeps you inspired? What scares you?

RP: What keeps me inspired is the heroism of the young women and men I met, and also the fact that I fell in love with Bangladesh, the way one does, inadvertently, with the people, the culture, even the insane traffic. I’m committed to social justice, and taking on this one issue and really working on it exclusively has kept me inspired. Also, I did put this on a long timeline. I wanted to accomplish one thing – the TakeActionFAST petition. Along the way I got to do some fun and meaningful art projects and meet so many extraordinary people.

The issue is off the radar of the media completely. This is what I call the Politics of the Aftermath. The media lurches from one disaster to the next, disaster porn as it’s been called, and no one seems to think of the long term after effects on the survivors of these horrific crises. I’m really counting on millennials to pick up the torch. I’m afraid that I’m just too much of an outlier – an artist trying to create a social justice campaign, not really encouraged by the local art world here, and a social justice activist who is an artist, so viewed skeptically, on occasion, by trade union people and activists, because I’m working alone. Everything I’m doing is hope and prayers that I can bridge these two complex communities.

If you’d like to support Robin and the campaign project, or learn more about her work and this community project, check out the project website here.

I particularly enjoyed seeing project photographs and listening to the audio recordings from interviews with workers, here.

While the campaign is live now, there will be a launch in Toronto in May. Here are the event details:

When? May 4 – May 5, 2017, 7 PM-12AM

Where? The Great Hall, 1087 Queen St. West, Toronto M6J 1H3 (at Dovercourt)

What?

- Online action campaign;

- Canadian and Bangladesh bands, singers, dancers and food;

- a pop up fashion market of indie Canadian designers;

- a ‘Mock Sweatshop’ where participants can sew giant t-shirts with garment workers from Workers United Canada;

- a Rana Plaza Memorial;

- and art by and about Bangladeshi garment workers