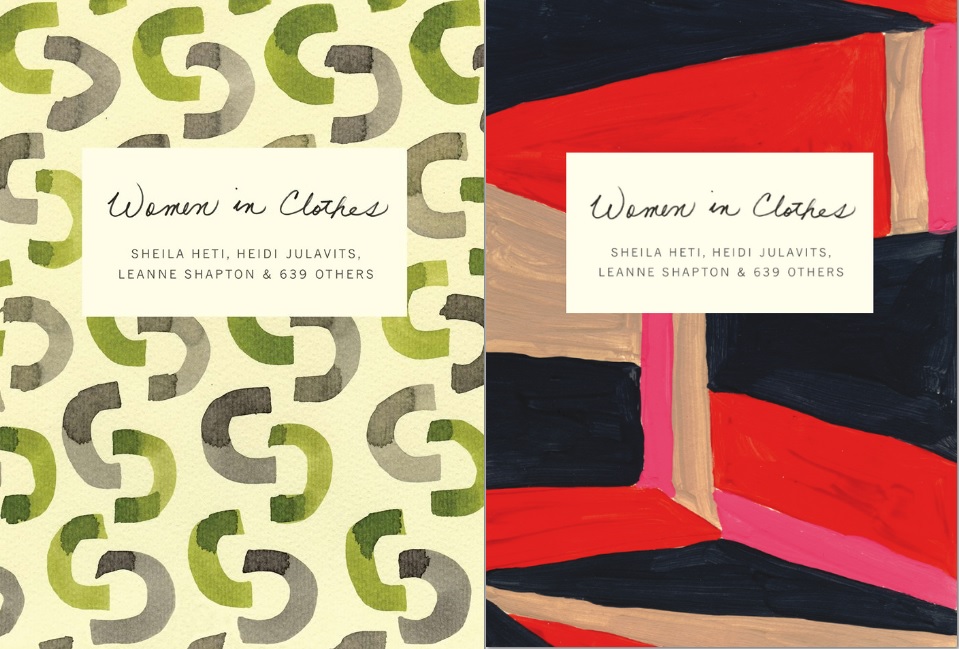

Hudson’s Bay Unveils Official Parade Uniforms for Canadian Olympic Team at Sochi 2014 Opening Ceremony (CNW Group/Hudson’s Bay Company)

There have been quite a few articles on the Sochi 2014 olympic fashion so let’s talk about the uniforms.

As a Canadian, I have mixed feelings about the uniforms designed by the Hudson’s Bay Company (HBC). The historical significance of this company, which predates the official establishment of Canada, cannot be underestimated. HBC’s history as a crown charter is so intertwined with that of the birth of the Canadian colonies that the two stories cannot be told separately. Our history curriculum inevitably discusses the voyageurs [fur trappers] and the Hudson’s Bay Company’s fur trading posts along Hudson Bay, usually as a starting point to the story of Canada [for more on that story, see here]. Yes, I recognize that this is a Euro-centric view that privileges the colonial settler experience over that of the original native inhabitants.

The Voyageurs by ONFB , National Film Board of Canada

Anyway, so the uniforms…actually, I’m mostly talking about the wool coats; those convey strong sense of symbolism for Canadians. The maple red with a bold black stripe are a direct reference to the iconic HBC blanket, as you’ll see in the video below by the Textile Museum of Canada. It was introduced in 1780 as a trading item at the fur trading posts and became very popular, particularly with the First Nations [read about that history here]. Since then, it has become quite literally a physical manifestation of Canadian identity – a difficult feat for a country that struggles with the question of identity.

Here is the issue with this uniform, and the HBC blanket in general, it embodies two narratives. On the one hand, it symbolizes an enduring link to the voyageurs and all that they represent – the spirit of exploration in a vast rugged wilderness, their strength and pride in the face of adversity, their determination to survive harsh winters which has now also become part of Canadian identity [seriously, people can recount the details of winters past], so much so that the Canadian Olympic Committee slogan for Sochi 2014 is #wearewinter accompanied by Canadian poetry that depicts these attitudes of winter survival. These are the positive associations invoked when our athletes wear this uniform, adding to the sense of Canadian pride and belonging to what Benedict Anderson called the ‘imagined community’.

However, the blankets also hold negative associations. There is evidence that the HBC blanket was linked to the infection of the First Nations people with smallpox at Fort Pitt during the Pontiac Rebellion.

This uniform, by association to the HBC blanket, embodies a hidden narrative linked to this aspect of a huge historical trauma inflicted on the First Nations. Are we acknowledging this trauma by celebrating the blanket’s heritage? This is problematic because as this commentary points out:

“Much of the colonial legacy has been swept under the rug, with Canada’s subaltern having little voice in the processes of historiography […] Those privileged by the outcomes of history have had the power to manipulate a symbol representing an inconvenient stain on Canada’s reputation. The erasure of the blanket’s genocidal connotations draws an uncomfortable parallel to the consistent oversight of the subaltern within discourses of Canadian history and identity.”

And this is why I am conflicted over this uniform.