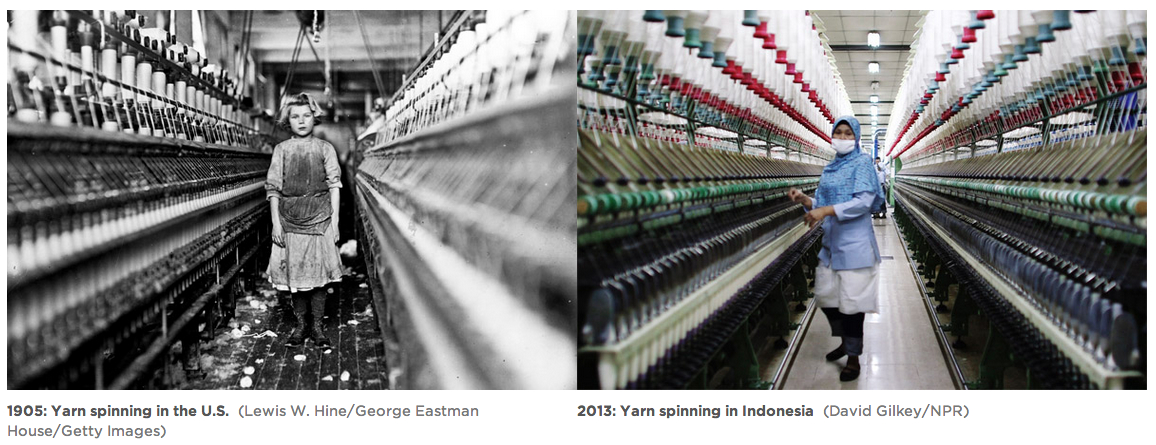

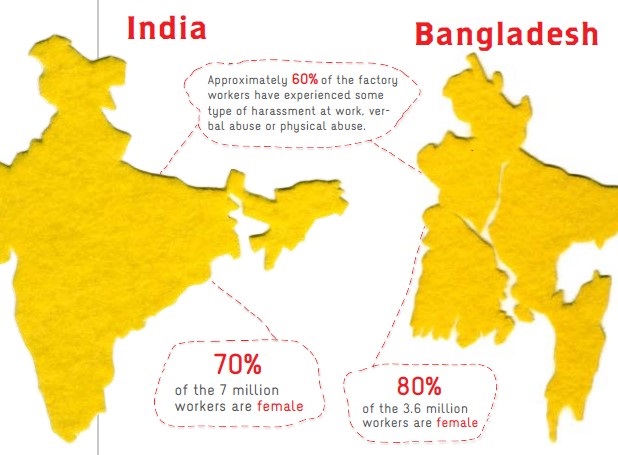

In light of the four year anniversary of the Rana Plaza collapse (April 24th), as well as International Workers’ Day (May 1st), I thought it would be a good time to share some new educational resources related to fashion and responsibility.

In light of the four year anniversary of the Rana Plaza collapse (April 24th), as well as International Workers’ Day (May 1st), I thought it would be a good time to share some new educational resources related to fashion and responsibility.

Ian Cook et al. of followthething.com have launched a free online course through FutureLearn: Who Made My Clothes? The 3-week course is designed to help learners think through systems of global fashion and apparel production and consumption, and to consider new ways of engaging with global supply chains. Here is the course introduction video explaining what’s on offer:

In an earlier blog post I shared a few thoughts on alternative forms of protest, highlighting Sarah Corbett and the Craftivist Collective. I mentioned that the School of Gentle protest would be launching soon…and it has! The course has already gone live, but you can still follow-along and participate. There are six classes, each with short video lessons, recommended readings and weekly assignments. For more information on these, see here and here. Here’s an introduction to the course:

I think what’s most interesting (and exciting) about these two initiatives, is that they strive to get learners interested in alternative forms of engagement. While so many responsible fashion education and campaign actions focus on consumer-based (user) approaches to change, these initiatives offer the potential to move things further, leaving space for learners to think through systemic challenges related to fashion and apparel production and consumption. The result is that learners are able to curate their own activist toolkit, with or without consumer-based strategies and actions.

The Social Alterations ‘Mind Map’ is one of our key resources designed to help you dig through to the root causes and consequences of a particular issue or challenge. We’d recommend keeping this resource on hand and using it in conjunction with the Who Made My Clothes? course and The School of Gentle Protest. You’ll find that resource for free in our Lab, here.

And with our Mind Map in hand, here are some additional resources to check out:

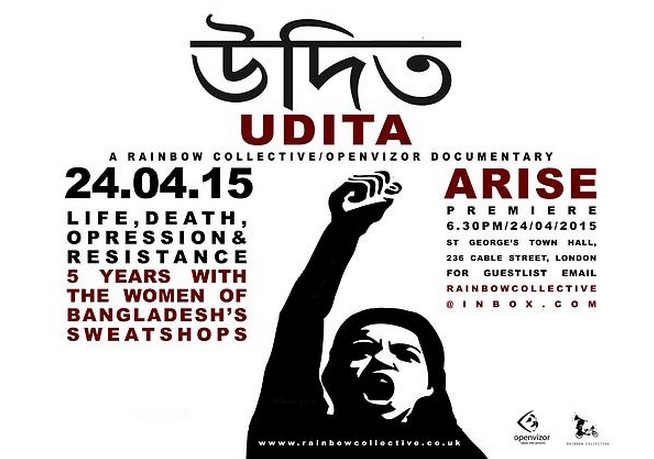

- “Fashion Exposed”: a serious of short videos filmed and directed by garment workers in Cambodia, supported by TRAID, Labour Behind the Label and the Rainbow Collective.

- “Behind the Seams”: a suite of free educational resources from TRAID, all available for download.

- Fashion Revolution offers a collection of free educational resources, developed by and in collaboration with Ian Cook and others.

And of course, if you haven’t already, be sure to check out all of the resources we have developed over the years. You’ll find these all available to download for free in our Learning Lab.

Happy learning everyone, hope it all leads to some creative disruption!